Plastic has already entered the food chain. Animals carry microplastics in their bodies. When they are themselves eaten, those microplastics are also ingested. This process is called ‘trophic transfer’ of microplastics. Since one animal eats another, microplastics can move through the food chain. The main question is what happens to the toxins and chemicals that are associated with these plastics.

Plastic in the food chain and bio-accumulation of pollutants

When plastic ends up in the environment, it tends to bind with environmental pollutants. With plastic that moves through the food chain, the attached toxins can also move and accumulate in animal fat and tissue through a process called bio-accumulation. In addition, chemicals are often added to plastic during the production process, to give them some desired properties. These chemicals can in turn leak from the plastic, even when that plastic is inside the body of an animal.

Toxins shared in the food chain

Plastic is by no means the only way that toxins, such as PCBs and dioxins, end up in the food chain. The role of plastic in bioaccumulation of toxins is quite small compared to exposure via the animals’ normal food. Animals that excrete swallowed plastic may actually cleanse their bodies because toxins present in the body have attached themselves to the plastic.

It is a different story for plastic additives. Unlike PCBs and dioxins, these substances have not accumulated in the food chain over the decades. When Japanese researchers found a particular flame retardant in the tissues of seabirds, it was certain that it came from swallowed plastic to which the flame retardant was once added.

Number of animals affected by plastic

The number of individual animals affected by plastic would be very difficult to estimate but would run into the billions. Attempts have been made to determine the number of species affected. In 2015, Dutch researchers found that the number of marine species that swallow or get caught in plastic had doubled since 1997: from 267 to 557. This number is now above 2000, with the caveat that only a very limited number of animal species have been investigated. It is even more difficult to determine whether plastic threatens the survival of a certain species, let alone the influence of plastic on the food chain.

Arrow worms

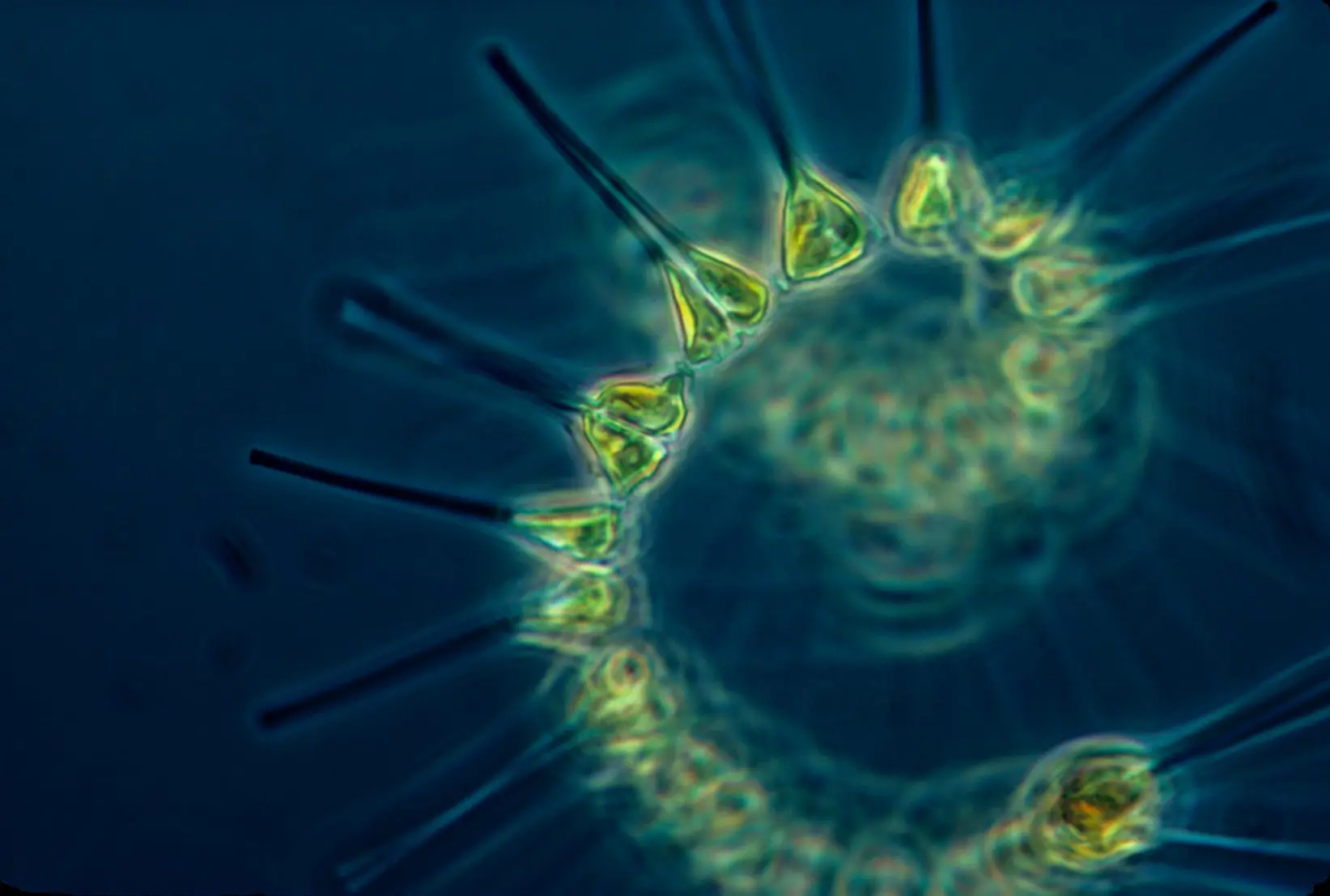

Arrow worms are transparent torpedo-shaped creatures which live in the sea and hunt for zooplankton.

As has been recorded on film, arrow worms consume plastic microfibers. The digestive tract of this animal is as long as its body. The curled fiber blocks the tube, with the result that the intake of real food is blocked. This recording shows how plastic enters the food chain because arrow worms are in turn eaten by animals higher up the chain. Amphipods that live at the deepest point of the ocean, the eleven-kilometer-deep Mariana Trench, were examined for the presence of plastic. These animals all had plastic in their bodies, almost always microfibers from synthetic clothing.

Plastic in fish and behavioural changes

Swedish scientists have shown that nanoplastics can enter the brains of fish through the food chain and lead to abnormal behavior. Nanoplastics in algae are eaten by water fleas, which in turn are food for fish. This is how plastic particles move through the food chain. The researchers made simulations of the food chain, with and without nanoplastics. In contrast to the fish that were not fed nanoplastics, the fish that did eat them showed abnormal behavior: slower eating and hyperactive behavior. It was a laboratory study, but the accumulation of plastic in living organs can also take place in nature, especially if the animals live for a long time. Fish that swim slower are easy prey. In this way, plastic can disrupt the natural balance.